Log #12: Oct/12/2024

- Wrappping up the DEMO

- 2D or 3D?

- Better Design Documentation

- Logical Maths

This week was pretty productive, our team mostly finishing the DEMO we've been working on. While the DEMO is super simple, it lays the groundwork for much of the project's functionality. It took longer than hoped, and there's some game-breaking bugs, but after this week, we finally have something sort of playable.

Along the way, a new teammate joined our team. The new member specializes in 2D art, so we were excited to be able to have someone who would work on the game's necessary 2D graphics. However, I quickly found that I was not used to making design documentation for our 2D artist. I did not even think about how a 2D artist would want to know if something should be hand-drawn or not...

We had a couple of hick-ups, eventually deciding to make one in-game object completely 2D. This process was confusing, but it did get our team to a place where adding images to 3D models made a lot more sense. I don't understand all the technical jargon, but now our artists have a better idea of what to do in order to put a 2D image on a 3D object.

Throughout this week, I also improved the game's design documentation. The written work stating how our game's setting should look is much more comprehensive, and now there's also way better documentaiont stating how the game's setting works.

MATH: Functions

I'm still not sure if this is the correct category of math for what I wanna write about. Welcome back to the MATH SEGMENT, where we're talking about logic!

I've been planning our game's beginning using flowcharts. I roughly lay out the logic that describes what should happen in-game, and then the programmers and artists make it a reality. In this MATH SEGMENT, I want to talk about how organizing the logic of the game can allow the player to make sneaky decisions, things that don't necessarily seem fair.

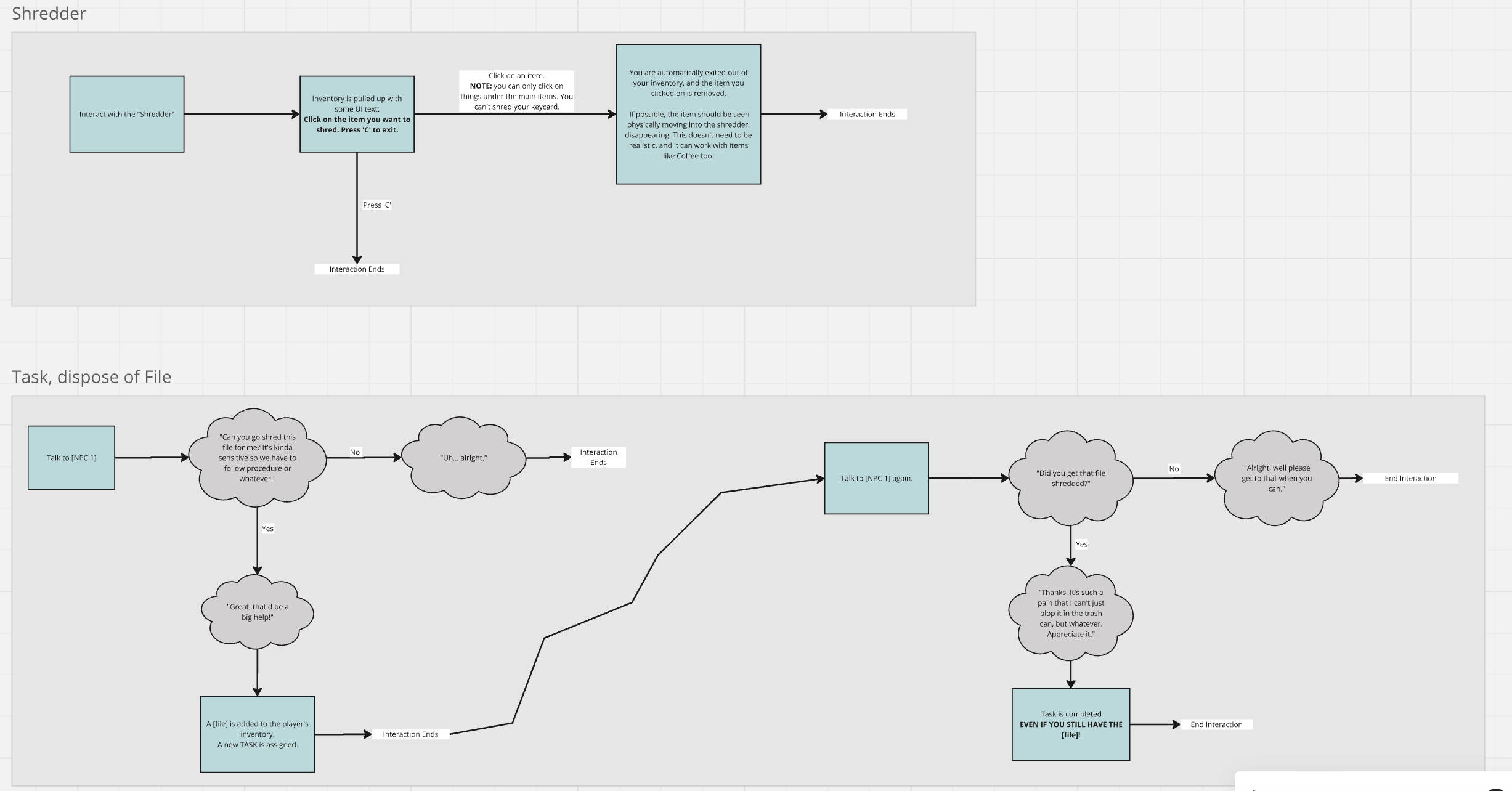

This week, I made a flowchart describing a task in our game where the player is prompted with delivering a file to a shredder in order to destroy it. I made two separate flowcharts, one describing the logic of interacting with the shredder, and another flowchart describing the interaction with the NPC.

For this in-game "task", the player has to talk to an NPC in order to be prompted with the option of taking the task. Then, they have to take the task, which grants them the file. From there, the player can return to the NPC, and state that the file has been disposed of, a 'YES' to which tells the game that the player has completed the task.

However, in this logic, note that the game never requires the player to do anything with the acutal file. All of the logical statements are based on how the player responds to NPC dialogue; they can do anything they want with the actual file. This allows the player to lie about what they are doing with the file they've been asked to dispose of.

While allowing the player to lie seems stupid, it makes the player feel more free, and can introduce more complex problems later down the line.

While planning out a game, carefully organizing what events are connected to others is super important. If we had defined the completion of this task by the file actually being destoryed, the player would not be able to lie about doing it.

This specific organization of logic has greatly influenced our DEMO. Our project's DEMO phase, as we're calling it, is essentially a much more complicated version of the above interactions. We have to be careful what events are tied to other events, otherwise we end up with confusing bugs that result in nonsense.

So there you have it, organizing logic carefully in order to allow our players to be dishonest. Pretty MATH-y, right?

MATH: Numbers and Quantity added Oct/24/2024

As you read above, adjusting to the use of 2D art was not a seamless change for our team. One important thing that required working out was the size to make our 2D images.

Our team's 3D artists already had figured out how to scale their models properly, but dealing with 2D images and a new artist took a little bit of adjustment.

As a designer, I need to tell the artist how big they need to make something. Artists want to know the measurements of their pieces, apparently. However, in order to know how big a 2D image needs to be, we need to look at the texel density on our models, which the resolution per unit space in our world.

In order to properly plan this out, we have to take the size that we want our image to be in-game, and then we can find the resolution of our image. For example, if we want 100 pixels to cover a 1 meter cube in our world, then if we have an image that is 2 meters tall, it should be 200 pixels long.

This requires thinking about the proper dimensions of our image. However, our game does not require a lot of exact measurements right now. When it comes to how big an image should be, for now, we aren't ready to be super precise. We need to get things in our world before we can precisely determine how big everything should be.

So, I resort to communicating in other, much more vague, ways. As we rough out the layout of our game, I have been measuring things in terms of our player, saying that a given image is "2 players tall," for example.

Because our game revolves around its player, measuring the world in terms of our player keeps our focus on what's most important, and it helps logically scale things in our world. For example, some of our walls are two or three players tall. That's pretty enormous. Being able to look at the world from the player's position, and figure out how big something should be is useful, and is a cool part of desiging our game.

Well, that's all for today, have a good one, and thanks for reading!

-Luke Knotts